G. Dž. Uells [P014]

Paratext collocation: Sobranie fantastičeskich romanov i rasskazov G. Dž. Uellsa v šesti tomach, t. 1 – Moskva, Leningrad – Zemlja i fabrika – pp. III-IX

Paratext's typology: Preface

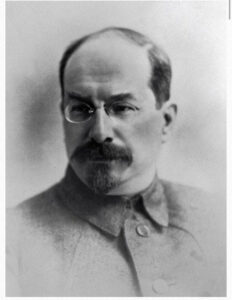

Author of the paratext: Lunačarskij Anatolij Vasil’evič

Author's bio:

Anatoly Vasilievich Lunacharsky (1875–1933) served as People’s Commissar for Education from 1917 to 1929; a writer and playwright, he also distinguished himself as a literary and theatre critic, translator, and art historian. A member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) from 1895, he joined the Bolshevik faction in 1903 and took an active part in the Revolution of 1905–1907 and in the October Revolution. Arrests and exiles marked his early years of political activity, during which he also began an intense journalistic and critical career. He collaborated with Bolshevik periodicals such as "Proletarij" and "Vperëd", was close to Aleksandr Bogdanov and, although linked to Lenin, soon came into conflict with him on philosophical and political grounds. In 1909 he was among the founders of the far-left group "Vperëd" and took part in the organisation of party schools for Russian workers in Capri and Bologna. In the years preceding the Revolution he developed a reflection on the relationship between Marxism and religion, known as “God-building” (bogostroitel’stvo), set out in the two volumes of Religija i socializm (Religion and Socialism, 1908–1911), in which he argued for the need to complement the scientific dimension of Marxism with an ethical and aesthetic component.

Alongside his political militancy, Lunacharsky consistently cultivated writing and literary criticism. Author of symbolist and religious plays such as Ivan v raju (Ivan in Paradise, 1920), and of a major project of historical drama, Oliver Kromvel’ (Oliver Cromwell, 1920), he also devoted numerous essays to Shakespeare, Goethe, and to Russian and European classics, interpreting them through the lens of Marxism. He served as editor of the arts section of the journal "Obrazovanie" (1906–1908) and contributed as a reviewer of Western European literature, standing out for his opposition to cultural chauvinism.

After the October Revolution he joined the Council of People’s Commissars and took over the leadership of Narkompros, a position he held until 1929. In this role he defended the historical and artistic heritage, encouraged publishing and the spread of reading, and supported the translation of world classics through the Vsemirnaja literatura (World Literature) project, directed by Gorky. He acted as a mediator between the Party and the intelligentsia, often defending artists and writers from repression and maintaining an inclusive attitude towards different cultural currents.

In the following years he held other leading cultural posts: he directed the Institute of Literature and Language of the Communist Academy, the Institute of Russian Literature of the Academy of Sciences, and was among the editors of the Literaturnaja ėnciklopedija (Literary Encyclopedia). He maintained relations with European writers and intellectuals such as Romain Rolland, George Bernard Shaw, Bertolt Brecht, and H. G. Wells, becoming a prominent figure also on the international cultural scene.

In September 1933 he was appointed plenipotentiary representative of the USSR in Spain, but was unable to take up the post for health reasons. He died of angina pectoris in Menton, France, in December of the same year, while travelling to his new diplomatic post.

Ilaria Aletto

Bibliography: R. Boer, God in the World: Lenin, Hegel, and the God-Builders, "The Heythrop Journal", 60 (2019), pp. 341-547; Yu.B. Borev, Lunacharsky, Moscow, Molodaya gvardiya, 2010; Al. Deich, Lunacharsky, in Kratkaya literaturnaya entsiklopediya, 1962–1978, (gl. red.) A.A. Surkov, Moscow, Sovetskaya entsiklopediya, 1967, vol. 4, pp. 448-453; S. Fitzpatrick, The Commissariat of Enlightenment: Soviet Organization of Education and the Arts under Lunacharsky. October 1917–1921, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1970; Lunacharsky, in Bolshaya rossiiskaya entsiklopediya: V 35 tt., 2004–2017, (gl. red.) Yu.S. Osipov, Moscow, Nauch. izd. Bolshaya rossiiskaya entsiklopediya, 2011, vol. 18, pp. 139-140; Lunacharsky, in Literaturnaya entsiklopediya: V 11 tt., 1929–1939, (otv. red.) A.V. Lunacharsky, Moscow, OGIZ RSFSR, Gos. slovarno-entsikl. izd-vo “Sov. entsikl.”, 1932, vol. 6, cols. 626-635.

Date of the paratext: 1930

Paratextual directives:

Author image:

Title of the original work translated into Russian: T. 1:When the Sleeper Wakes, 1899. The First Men in the Moon, 1901. The War of the Worlds, 1897. T. 2:In the Days of the Comet, 1906. The War in the Air, 1908. In the Abyss, 1896. In the Avu Observatory, 1894. The Story of the Late Mr. Elvesham, 1896. Æpyornis Island, 1894. T. 3:Men Like Gods, 1923. Mr. Blettsworthy on Rampole Island, 1928. The Wonderful Visit, 1895. T. 4:The Invisible Man, 1897. The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth, 1904The Time Machine, 1895. A Story of the Days to Come, 1899. T. 5:The Island of Dr. Moreau, 1896 г. Т. 5The Dream, 1924. A Story of the Stone Age, 1897. The Flowering of the Strange Orchid, 1894. Under the Knife, 1896. The Red Room, 1896. The Remarkable Case of Davidson’s Eyes, 1895. The Lord of the Dynamos, 1894. The Plattner Story, 1896. The Truth About Pyecraft, 1903. Pollock and the Porroh Man, 1895. The Sea-Raiders, 1896. T. 6:The Man Who Could Work Miracles, 1898. The Apple, 1896. The Star, 1897. The Crystal Egg, 1897. The Purple Pileus, 1896. The Moth, 1895. The Stolen Bacillus, 1894. The Hammerpond Park Burglary, 1894. The Triumphs of a Taxidermist, 1894. A Deal in Ostriches, 1894. Through a Window, 1894. The Temptation of Harringay, 1895. The Flying Man, 1895. The Diamond Maker, 1894. The Autocracy of Mr. Parham, 1930. The Treasure in the Forest, 1894. The Empire of the Ants, 1905. A Catastrophe, 1895. The Jilting of Jane, 1928. The Sad Story of a Dramatic Critic, 1895. The Cone, 1895. The New Accelerator, 1901. The Magic Shop, 1903. Mr. Skelmersdale in Fairyland, 1909.

Publication date of the original work: 1895-1928

Country of the original work: United Kingdom

Author of the original text: Wells Herbert George

Bio of the Author (original text):

Herbert George Wells (1866-1946), British writer, journalist and essayist, is considered one of the founding fathers of science fiction. Wells explored themes of scientific progress, its ethical and social implications, as well as dystopia and social criticism in his writings. His vast and varied literary output ranges from novels to non-fiction, and is characterised by a marked ability to anticipate the major themes and challenges of the future. Wells' works are intrinsically linked to the great social and technological transformations of his era. Born in Bromley, Kent, Wells came from a family of modest means. After a childhood marked by financial difficulties and an irregular schooling, he managed to obtain a scholarship to the Normal School of Science in London (now part of Imperial College), where he studied biology under Thomas Henry Huxley, a leading proponent of Darwinian evolutionism. This experience profoundly influenced his worldview and literary production. H.G. Wells made his debut as a novelist in 1895 with The Time Machine, a pioneering work that laid the foundation for the modern science fiction genre by introducing the concept of time travel. Other highly successful novels followed, such as The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897) and The War of the Worlds (1898), which, while falling within the genre of adventure fiction, proved to be powerful instruments of social criticism, offering a sharp analysis of the vices and contradictions of Victorian society. In the course of his career, Wells broadened his literary horizon, also devoting himself to realistic fiction, with novels such as Kipps (1905) and Tono-Bungay (1909), and to non-fiction, dealing with topics such as politics, history and science. Among his most influential essays are The Outline of History (1920) and The Open Conspiracy (1928), in which he outlined his vision of a rational and scientific world order.

Wells had a complex relationship with the Soviet Union, which he visited several times, showing an alternating interest between curiosity and criticism. His first visit was in 1914, shortly before the outbreak of World War I, when he travelled to Russia to closely observe the political and social conditions of the Tsarist Empire. This trip provided him with an initial contact with the Russian reality and helped shape his views on the need for radical change. In 1920, he returned to post-revolutionary Russia motivated by a great interest in the transformations taking place. During this trip he met Vladimir Lenin, with whom he had a conversation about revolution, socialism and the role of science in Soviet society. Wells was impressed by Lenin's intelligence and analytical lucidity, while maintaining reservations about the new system's real chances of success. His observations on this experience were collected in the book Russia in the Shadows (1920), in which he described the difficult economic and social conditions in post-revolutionary Russia and the chaos resulting from the civil war. This text, although lacking open condemnation, highlighted the fragility of the new Soviet state and sparked a heated debate between Western and Soviet intellectuals. In 1934, Wells returned to the Soviet Union for a second major trip, during which he met Josef Stalin. The meeting with Stalin on 23 July in Moscow was characterised by a long dialogue in which Wells asked direct questions about economic policy, industrialisation and the role of the individual in the socialist state. Stalin presented himself as a pragmatic leader, committed to the modernisation of the USSR, emphasising the success of the five-year plan. Wells, unlike other Western intellectuals, was initially optimistic about Stalin's leadership, seeing him as a builder of a new social order. However, in later years, he became more critical of the Soviet regime, especially with regard to political repression, the lack of freedom of expression and the ideological rigidity imposed by the government.

In Russia and the Soviet Union, Wells' works were translated and published with great interest from the early years of the 20th century. His science fiction fascinated Russian audiences, while his socio-political writings were carefully analysed by intellectuals and Soviet government officials. After the October Revolution, Wells was seen as an author who reflected the tensions between scientific progress and social transformation, and his works were published with increasing attention from Soviet publishers. However, his critical stance towards Stalinism led, in the following years, to a decreased circulation of his texts in the USSR, especially those of a political nature. The debate on Wells among Soviet critics oscillated between recognition of the value of his scientific insights and ideological suspicion of his ideas on liberalism and world governance. An active supporter of socialism and a strong critic of the capitalist system, elements that emerge in many of his works, in the last years of his life he manifested a growing pessimism towards the future of humanity, marked by the advent of World War II and the threat of nuclear weapons.

Wells' works have had a lasting impact not only on science fiction literature, but also on popular culture and political thought in the 20th century. His ability to anticipate scientific and technological developments, combined with a profound reflection on the human condition, has made his novels still relevant today and the subject of numerous film adaptations and film adaptations.

Ilaria Aletto

Bibliography: R. Cockrell, Future Perfect: H. G. Wells and Bolshevik Russia, 1917–32, in The Reception of H. G. Wells in Europe, eds. P. Parrinder, J.S. Partington, New York, Thoemmes Continuum, 2005, pp. 74-90; G. Diment (ed.), H. G. Wells and All Things Russian, London, Anthem Press, 2019; Ju. Kagarlickij, Vgljadyvajas’ v grjaduščee: Kniga o Gerberte Uėllse, Moskva, Kniga, 1989; M. Kozyreva, V. Shamina, Russia Revisited, in The Reception of H. G. Wells in Europe, eds. P. Parrinder, J.S. Partington, New York, Thoemmes Continuum, 2005, pp. 48-62; A. Ljubimova, B. Proskurnin, H.G. Wells in Russian Literary Criticism, 1890s–1940s, in The Reception of H. G. Wells in Europe, eds. P. Parrinder, J.S. Partington, New York, Thoemmes Continuum, 2005, pp. 63-73; N.C. Nicholson, H.G. Wells, in Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/H-G-Wells (accessed 5 October 2025).

Title of the Russian translation: Tom 1:Kogda Spjaščij prosnëtsja (traduttore non indicato, red. M. Zenkevič) Pervye ljudi na Lune (traduttore non indicato, red. M. Zenkevič) Vojna mirov (trad. I. Magur) Tom 2:V dni komety (trad. V. Zasulič) Vojna v vozduche (trad. Ė. Pimenova) Na dne okeana (trad. Ė. Pimenova) Observatorija na Avu (trad. Ė. Pimenova) Ispoveď pokojnogo mistera Ėlvzchema (trad. Ė. Pimenova) Ostrov Ėpiornisa (trad. Ė. Pimenova) Tom 3:Ljudi kak bogi (trad. A. Karnauchova, red. M. Zenkevič) Mister Bletsuorsi na ostrove Rėmpol' (trad. S. Zajmovskij) Čudesnoe poseščenie (trad. M. Likiardopulo) Tom 4:Čelovek-nevidimka (trad. D. Vejs) Pišča bogov (trad. V.G. Tan) Mašina vremeni (trad. K. Morozova) Grjaduščie dni (trad. V.G. Tan) Tom 5:Ostrov doktora Moro (trad. K. Morozova) Son (trad. R.F. Kullė) 50 tysjač let nazad. Rasskaz iz kamennogo veka (trad. N. Morozov) Strannaja orchideja (traduttore non indicato) Pod nožom (traduttore non indicato) Krasnaja komnata (traduttore non indicato) Porazitel’nyj slučaj s glazami Devidsona (traduttore non indicato) Bog Dinamo (traduttore non indicato) Istorija Plattnera (traduttore non indicato) Pravda o Pajkrafte (traduttore non indicato) Čelovek iz plemeni Porro (traduttore non indicato) Morskie piraty (traduttore non indicato) Tom 6:Čelovek, kotoryj mog tvorit’ čudesa (traduttore non indicato) Jabloko (traduttore non indicato) Zvezda (traduttore non indicato) Chrustal’noe jajco (traduttore non indicato) Krasnyj grib (traduttore non indicato) Babočka Genus Novо (traduttore non indicato) Pochiščenie bacilly (traduttore non indicato) Nalët na Chėmmerpond Park (traduttore non indicato) Toržestvo taksidermii (traduttore non indicato) Sdelka so strausami (traduttore non indicato) Iz okna (traduttore non indicato) Iskušenie Herringea (traduttore non indicato) Letajuščij čelovek (traduttore non indicato) Čelovek, delajuščij brillianty (traduttore non indicato) Samoderžavie mistra Pargema (red. S. Zajmovskij) Sokrovišče v lesu (traduttore non indicato) Murav’inaja imperija (traduttore non indicato) Katastrofa (traduttore non indicato) Pokinutaja nevesta (traduttore non indicato) Pečal’naja istorija teatral’nogo kritika (traduttore non indicato) Nad žerlom domny (traduttore non indicato) Novejšij uskoritel’ (traduttore non indicato) Volšebnaja lavka (traduttore non indicato) Mister Skelmersdejl v carstve fej (traduttore non indicato)

Collocation of the translation: Moskva-Leningrad – Zemlja i fabrika

Translator's name: Alla Mitrofanovna Krainskaja (Karnauchova), Robert Fridrichovič Kullė, Michail Fëdorovič Likiardopulo, I. Magur (NA), Nikolaj Aleksandrovič Morozov, Ksenija Alekseevna Morozova, Ėmilia Kirillovna Pimenova, Vladimir Germanovič Bogoraz (Tan), David L’vovič Vejs, Semën Grigor’evič Zajmovski, Vera Ivanovna Zasulič, Michail Aleksandrovič Zenkevič (red.)

Translator's bio:

Vladimir Germanovich Bogoraz (1865-1936), known by the pseudonym Tan-Bogoraz, was a prominent revolutionary, writer, translator, ethnographer and linguist, and a central figure in the cultural and scientific life of early 20th century Russia. He was a professor at the Leningrad State University and an active member of the Academy of Sciences. He studied at the Gymnasium in Taganrog together with Anton Chekhov. After graduating in 1880, he initially enrolled in the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics at the University of St. Petersburg, before moving to the Faculty of Law. In 1881, he joined the circles of the Narodnaya Volya (People's Will) and, from 1885, actively participated in its revolutionary activities, contributing to the underground press. Arrested several times, in 1889 he was sentenced to ten years of exile in Srednekolymsk. During his period of confinement, Bogoraz undertook in-depth studies of ethnography, gaining such recognition that in 1894 he was included in the 'Sibiryakov Expedition' of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, dedicated to the study of the indigenous peoples of north-eastern Eurasia, in particular the Chukchi. Between 1895 and 1897, he lived among the Chukchi, collecting valuable anthropological and linguistic material. Later, in 1900, he was sent by the Academy on an expedition to the North Pacific. At the same time, he started his literary career in 1896, publishing essays, short stories and poems. His first book of prose, Chukotskich rasskazach (Tales of Chukotka, 1899), and his first collection of poetry, Stikhi (Verses, 1900), received much attention. In 1899, he emigrated to the United States, where he participated in an ethnographic expedition to the Far East under the guidance of anthropologist Franz Boas. Here he collected material on the Chukchi, the Koryaks, the Itelmeni and the Eskimos. From 1899 to 1904 he worked as curator of the ethnographic collection of the American Museum of Natural History; in 1904 he published the monograph The Chukchee, which became a seminal work on the ethnography and mythology of this people. In the United States, he also took an interest in the Duchobory community that emigrated to Canada between 1898 and 1899 to escape Tsarist persecution. His essays on this community, considered an example of peasant socialism, were collected in the volume Duchobory v Kanade (The Duchobory in Canada, 1904). In 1905, he was one of the founders of the Peasants' Union and in 1906 participated in the creation of the Labour Group in the First State Duma, although he was not elected as a deputy. During those years, he wrote numerous populist and propagandist essays and articles. During the 1905 revolution, he collaborated with the newspaper of the Bolshevik military organisation "Kazarma", publishing poems that were widely circulated among the revolutionaries. After the October Revolution, he took up positions close to the Smena vech movement through the magazines "Rossiya" and "Novaya Rossiya". In 1918, he became a researcher at the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography of the Academy of Sciences and, from 1921, he taught at various universities in Leningrad, in particular at the Ethnography Department of the Institute of History, Philosophy and Linguistics. In 1929, he founded the Northern Peoples Institute, where he taught general ethnology. He also promoted the creation of the Committee for Assistance to the Peoples of the Northern Periphery (Northern Committee), which was established at the Pan-Russian Central Executive Committee (VCIK) to foster the economic, administrative, judicial and cultural-health development of the northern peoples. In the academic year 1927/28, together with Sergei Nikolayevich Stebnitsky, he compiled the first Russian language manual for schools in the North. In the last years of his life he was director of the Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism, which he founded in 1932 and housed until 2000 in the Kazan Cathedral in St. Petersburg. Parallel to his scientific work, Bogoraz distinguished himself as a translator. Between 1909 and 1917, he edited and translated numerous works by H.G. Wells for the thirteen-volume edition published by the Petersburg publishing house 'Shipovnik' between 1909 and 1917 (Sobranie sochinenij v 13-ti tt., Collection of Works in 13 Volumes). His translated texts include: The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth (Pishcha bogov), Kipps (Kipps), Tono-Bungay (Tono-Bange), The History of Mr. Polly (Istoriya mistera Polli), and The War in the Air (Voyna v vozduche).

Bibliography: K. Gernet, V.G. Bogoraz (1865–1939). Eine Bibliographie, München, Mitteilungen des Osteuropa-Instituts München, 1999; Materialy po V.G. Bogorazu, ed. by Vjač. Vs. Ivanov, “Russkaya antropologicheskaya shkola”, https://kogni.narod.ru/bogoraz.htm (last access: 5 October 2025); A.M. Reshetov, Bogoraz Vladimir Germanovich, in Bol’shaya rossiyskaya entsiklopediya, 2017, https://bigenc.ru/c/bogoraz-vladimir-germanovich-47eb92

(last access: 5 October 2025).

Alla Mitrofanovna Krainskaya (Karnauchova) (1877-1958) was born in Kiev. His father, Mitrofan Evgrafovich Krainsky, was the editor of the magazine "Iskusstvo i Zhizn'" and the newspaper "Zhizn' i iskusstvo". In 1922, she moved to Petrograd, where she worked as director of the publishing house "Mysl'". She began translating in 1924 and collaborated with the magazine "Vestnik inostrannoy literatury". She translated works by H.G. Wells, Strindberg, H. Mann, London, Hardy, de Kruif, Viebig, O. Henry, Chesterton, Bret Harte, Galsworthy and Tagore. She also edited and adapted works of foreign literature for children. She died in 1958 in Leningrad.

Bibliography: K. Chukovsky, Literaturnye vospominaniya, Moscow, Sovetskiy pisatel’, 1989, p. 17; Pisateli Leningrada: Biobibliograficheskiy spravochnik. 1934–1981, ed. by V. Bakhtin, A. Lur’e, Leningrad, 1982, p. 148.

Robert Fridrichovich Kullė (1885-1938), literary historian, lecturer, critic and translator. Born in St. Petersburg, he was the son of Fëdor (Frédéric) Andreyevich Kullė, French by origin, artist of the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre. After graduating from the Imperial Institute of History and Philology in St Petersburg, he worked from 1918 to 1923 as a professor and director of the Faculty of the History of Western European Literature at the University of Tashkent, of which he was one of the founders. In 1923 he returned to Petrograd with his wife and two daughters, supporting himself by giving lessons at the State Pedagogical Institute "Gercen", the Institute of the Living Word (Institut zhivogo slova) and the Institute of the Civil Air Fleet. Between 1926 and 1934, he collaborated with the publishing house "Vremiya" and several literary journals, including "Noviy Mir", "Zvezda", "Okt'yabr", "Sibirskie ogni", "Vestnik znaniya" and "Vestnik inostrannoy literatury", also contributing to the Literary Encyclopaedia (Literaturnaya ėntsiklopediya). He was an associate of poets such as Klyuev, Yesenin and Mayakovsky. From 1924 to 1932, he kept a diary on events in the Soviet Union, in which he often targeted Bolshevik power, in his eyes responsible for the decadence of Russian culture. In 1934, he was arrested as part of the 'delo slavistov' - among the most extensive Stalinist repressions that involved the academic and cultural intelligentsia in the late 1930s and early 1950s in the USSR - and his diary and manuscripts of the volume Studies on Contemporary Western European Literature (Ėtyudy o sovremennoy zapadno-evropeyskoy literatury, M-L., GIZ, 1930) were confiscated. Initially sentenced to death, the sentence was commuted to ten years in a prison camp. In 1938 he was executed in the Uchta-Pechora camp (UPITLag). He was rehabilitated in 1956.

Bibliography: Kullė, in Literaturnaya ėntsiklopediya: V 11 tt., 1929–1939, A.V. Lunacharsky (otv. red.), Moscow, Izd-vo Kom. Akad., 1931, vol. 5, cols. 722-723; Kullė Robert Fridrikhovich (Fredrikhovich), in Elektronnyy arkhiv Fonda Iofe (Otkrytyy obshchestvennyy arkhiv po istorii sovetskogo terrora, Gulaga i soprotivleniya rezhimu), https://arch2.iofe.center/case/1214 (last access: 5 October 2025).

Mikhail Fyodorovich Likiardopulo (literary pseudonym M. Richards) (1882-1925), Russian journalist, translator, literary critic and playwright of Greek descent, a prominent figure in the Moscow Symbolist circle of the first decades of the 20th century. His contribution to Russian culture was particularly significant, both in the literary and theatrical spheres, where he played a crucial role in mediating between Russia and the West. Likiardopulo was an active contributor to the journal "Vesy", one of the most significant organs of Russian symbolism, and served as secretary of the Moscow Art Theatre from 1910 to 1917. Alongside these assignments, he continued to work as a journalist and political analyst, publishings articles in newspapers such as "Nov'", where he headed the Foreign Department in 1914, "'Den'" and "Utro Rossii". In 1912, he became active in the Russian secret service, which led him to take on tasks more directly related to diplomacy. In 1916, he moved to Stockholm, where he assumed responsibility for the Press and Propaganda Department at the Greek diplomatic mission, while continuing his collaboration with the Russian press. After the discovery of the Lockhart conspiracy in 1918 and his subsequent departure from the Soviet government, Likiardopulo moved to London, where he began working as a correspondent for the British newspaper "The Morning Post" in 1919. According to some sources, he had links with British intelligence, from which he allegedly derived UK citizenship. In the field of translation, Likiardopulo played a key role in introducing Western authors into Russian and Soviet culture. One of his most famous translations is Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (Portret Doriana Greya), published in 1909 under the pseudonym M. Richards within the Polnoe sobranie of Wilde's works, edited by Korney Chukovsky.

Bibliography: K.M. Azadovsky, D.E. Maksimov, Bryusov i “Vesy” (K istorii izdaniya), in Literaturnoe nasledstvo, vol. 85: Valeriy Bryusov, Moscow, Nauka, 1976, p. 282; E. Vyazova, “Gipnoz anglomanii”: Angliya i “angliyskoye” v russkoy kul’ture rubezha XIX–XX vekov, Moscow, Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2009, pp. 228–229; T.V. Pavlova, Oskar Uayl’d v russkoy literature (konets XIX – nachalo XX veka), in Na rubezhe XIX i XX vekov, Leningrad, Nauka, 1991, pp. 103-113.

Nikolai Aleksandrovich Morozov (1854-1946) was a Russian revolutionary, science populariser, writer and poet. A prominent figure in populist movements, he was a member of the Tchaikovsky Circle and participated in the activities of the organisations Zemlya i Volya (Land and Freedom) and Narodnaya Volya (People's Will). During his militancy, he devoted himself to theoretical reflection on political terrorism, publishing the pamphlet The Terrorist Struggle (Terroristicheskaya bor'ba, London, Rus. tip., 1880), in which he analysed the role of terror as a revolutionary tool. His ideas had a lasting influence that can be seen in the socialist-revolutionary currents of the first decades of the 20th century. In 1882, during the 'Trial of the Twenty' brought against members of Narodnaya Volya, Morozov was sentenced to life imprisonment for his subversive activities and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress and Shlisselburg, spending a total of around thirty years in prison, twenty-five of them in solitary confinement. After liberation in 1905, he approached the Constitutional Democratic Party (Cadets), whose reformist positions reflected his now changed thinking. Although he remained a prominent figure in the intelligentsia, he did not join the Social Democratic Workers' Party. Parallel to his political activity, Morozov devoted himself to the natural sciences, publishing numerous studies in the fields of physics, chemistry and astronomy. His major works include Revelation in Thunder and Storm (Otkrovenie v groze i bure, M., V.M. Sablin, 1907), Prophets (Proroki, M., Tip. I.D. Sytina, 1914) and the monumental seven-volume Christ (Christos, M.-L., Socėkgiz, 1924-1932), in which he developed a theory according to which the biblical texts were a reflection of medieval astronomical observations and hypothesised a radical revision of historical chronology. His ideas later influenced the proponents of the New Chronology. Morozov enjoyed a certain recognition in the Soviet cultural scene: in 1918, he was appointed director of the P.F. Lesgaft Institute of Natural Sciences, whose scientific station was located on his estate in Borok, in the Yaroslavl oblast. In 1932, he became an honorary member of the USSR Academy of Sciences and was awarded the title of Scientist Emeritus in 1934. He was also active in the literary community, participating, for example, in the Literary Fund (Literaturniy fond). In addition to his scientific and revolutionary output, Morozov also distinguished himself as a translator. Together with his wife, Mariya Vasilyevna Morozova, he contributed to the spread of English scientific and fantasy literature in Russia, translating works by Wells. His translations include the novel The Time Machine (Mashina vremeni, in 1909) and the short story A Story of the Stone Age (50 tisyach let nazad. Rasskaz iz kamennogo veka, in 1930). His memoirs and revolutionary poetry were appreciated at the beginning of the 20th century by authors such as Lev Tolstoy, Valery Bryusov and members of the OBERIU group, while they drew negative criticism from Aleksandr Blok, Nikolai Gumilëv and Vasily Rozanov. His figure remains emblematic for his role in revolutionary movements and for his contribution to scientific popularisation and historical revision.

Kseniya Alekseyevna Morozova (née Borislavskaya; 1880-1948), Russian pianist, writer, journalist, poet, translator and memoirist. Wife of academician, poet and writer Nikolai Morozov. A graduate of the St. Catherine's Institute and the St. Petersburg Conservatory, she performed in Europe as a pianist. From 1907 to 1911, she collaborated with the newspaper "Russkie Vedomosti". She translated Pierre Louÿs' novel Aphrodite (1896, in Russian Aphrodita), Knut Hamsun and Wells' works (Mashina vremeni and Ostrov doktora Moro, both published in the 1930 collection edited by Zenkevich) into Russian.

Bibliography: A.V. Lunacharsky, Perepiska po voprosu ob izdanii knigi N.A. Morozova Khristos, “Istoriya SSSR”, 1965, no. 2, p. 86; N.A. Morozov, in Isaran: Informatsionnaya sistema “Arkhivy Rossiyskoy Akademii nauk”, 2017, https://isaran.ru/?q=ru/person&guid=01B09D95-1615-70BB-D37E-1B6AA6D22703 (last access: 5 October 2025); A.P. Shikman, Nikolay Morozov. Mistifikatsiya dlinoiu v vek, Moscow, Ves’ Mir, 2016.

Ėmilia Kirillovna Pimenova (1854-1935), Russian journalist, writer and translator, author of works on socio-political topics, as well as compiler of geographical and ethnographic publications. She played an important role in Russian journalism and was a promoter of new methods and techniques in journalistic work. One of the few female publicists of the time, Pimenova distinguished herself by repeatedly addressing the question of women's position in bourgeois society, soon joining the struggle for women's emancipation.

Bibliography: Pimenova, Ėmiliya Kirillovna, in Ėntsiklopedicheskiy slovar’ Brokgauza i Ėfrona: V 86 tt., 1890–1907, dop. vol. 2, St. Petersburg, 1906, p. 409; Pimenova, Ėmiliya Kirillovna, in Russkie pisateli. 1800–1917: Biograficheskiy slovar’, ed. by P.A. Nikolaev, Moscow, Bol’shaya rossiyskaya entsiklopediya, 1999, vol. 4, pp. 604-606.

David Lvovich Veys (Vays ) (David-Tevel' Ėfroimovich-Leyzerovich) (1878-1938), translator, editor and Soviet public education official. He worked for "Shipovnik" from 1906 to 1917, a period when the publishing house was particularly busy publishing works of European fiction and culture. In the period between 1920 and 1922, Veys held the position of deputy director at the State Publishing House (Gosizdat) and then became its authorised representative in Petrograd. Subsequently, he held prominent positions in the publishing industry from 1922 to 1924. Between 1925 and 1926, he was deputy chairman of the board of the publishing house 'Priboy' in Leningrad. From June 1926 to January 1929, he headed the publishing house 'Ėkonomicheskaya Zhizn', and during the same period, until December 1930, he headed the publishing house 'Bezbozhnik'. From the end of 1927, he worked as assistant to the editor-in-chief of the Small Soviet Encyclopaedia (Malaya Sovetskaya entsiklopediya). In January 1931, he was appointed director of the state publishing house of medical and biological literature ('Biomedgiz') and member of the Ogiz board of directors. In December 1937, Veys was arrested on charges of participation in an anti-Soviet terrorist organisation. In August 1938, he was sentenced by the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the USSR and executed the same day at the Kommunarka. His translation of Wells's The Invisible Man, which first appeared in 1910 in the 13-volume Collected Works (Nevidimka, vol. 10), was an important introduction to science fiction literature in pre-revolutionary Russia, and the novel, with its reflections on power, identity and alienation, was well suited to the social and political anxieties of the time.

Bibliography: Veys, David Lazarevich, in Ukazatel’ arkhiva NIPC “Memorial” (Moscow), https://archive.memo.ru/ВЕЙС-ДАВИД-ЛАЗАРЕВИЧ-1878-22-08-1938-,-ID:-RU12707902-pers-41194 (last access: 5 October 2025).

Semyon Grigoryevich Zaymovsky (1868-1950), Russian writer, scholar and translator. Author of the Anglo-Russian Desk Dictionary with pronunciation (Nastol'niy anglo-russkiy slovar' s ukazaniem proiznosheniya, Berlin, Izd. T-va Glinsman,1923) and the collection Winged Words: handbook, quotations and aphorisms (Krylatoye slovo: spravochnik, citaty i aforizmy, M.-L., Gos. izd-vo, 1930), in 1928 Zajmovsky also translated Poems from Kipling's The Jungle Book (Stichotvoreniya iz Knigi dzhungley). During the 1930s he devoted himself instead to translations of Wells' novels and short stories: 1930 saw the publication of his version of Mr. Blettsworthy on Rampole Island (Mister Bletsuorsi na ostrove Rėmpol'); in 1935 he translated The Door in the Wall (Kalitka v stene) and, three years later, The Shape of Things to Come (Oblik gryadushchego).

Bibliography: L.V. Antik, S.G. Zaymovskiy, in Moskovskiy knigoizdatel’ V.M. Antik: Katalog izdaniy 1906–1918, Moscow, Izdatel’stvo MIP, 1993, p. 14; S.G. Zaymovskiy, Istoriya izdatel’stva “Vsemirnaya literatura” v dokumentakh: Sud’by tvorcheskoy intelligentsii Rossii v postrevolyutsionnom prostranstve skvoz’ prizmu izdatel’skogo proekta Maksima Gor’kogo, 2021, https://vsemirka-doc.ru/component/tags/tag/zajmovskij/ (last access: 5 October 2025).

Vera Ivanovna Zasulich (1849-1919), writer, publicist, literary critic and translator, also active in the socialist movement. After a period of intense political engagement, she devoted herself to literature, criticism and translation, contributing to the spread of Marxism and Enlightenment thought in Russia. Her early writings included speeches and essays on historical and political topics. In 1881, she commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Polish uprising of 1831 with a speech, later translated into Polish and published in the collection Biblioteka Równosci (Geneva, 1881). Later, she delved into non-fiction and literary criticism, writing monographs on Rousseau (Russo, 1899; second edition, 1923) and Voltaire (Vol'ter. Ego Zhizn' i Literaturnaya deyatel'nost',1893; second edition, 1909), in which she analysed the role of the two philosophers in the formation of revolutionary thought. Her critical studies include essays on Dmitry Pisarev (1900), Nikolai Chernyshevsky and Sergei Kravchinsky (Stepnyak). She also wrote reviews of literary works, including Vasily Slepcov's Trudnoye vremya (1897) and Pyotr Boborykin's Po-drugomu. She collaborated with the journal "Iskra", contributing articles on important figures in Russian political and revolutionary culture, including Nikolai Dobrolyubov. Zasulich was also involved in translation, making the works of Marx and Engels accessible in Russia, thus promoting the dissemination of Marxist theories and actively participating in international theoretical debates. In the field of fiction, she introduced authors such as Wells to the Russian public with the translations Bog Dinamo (1909), V dni komety (1910) and Nevidimka (1910). She also worked on the Russian translation of Voltaire's philosophical novel Le Taureau blanc (1774). In her later years, he continued to write and translate, despite facing financial difficulties and health problems. After the October Revolution of 1917, she took a critical stance towards the Bolshevik regime, which she considered a deviation from the democratic revolutionary process. She devoted herself to writing her memoirs, which were published posthumously. Her contribution remains relevant to both the spread of Marxist ideas in Russia and the introduction of Western literature.

Bibliography: L.S. Fedorchenko, Vera Ivanovna Zasulich: Zhizn’ i deyatel’nost’, Moscow, Novaya Moskva, 1926; B.S. Itenberg, Zasulich Vera Ivanovna, in Bol’shaya sovetskaya entsiklopediya, A.M. Prokhorov (gl. red.), 1969, vol. 9, cols. 1134-1135; A.F. Koni, Vospominaniya o dele V. Zasulich, Moscow-Leningrad, Academia, 1933; N.A. Troitskiy, Zasulich Vera Ivanovna, in Bol’shaya rossiyskaya entsiklopediya, 2004–2017, https://old.bigenc.ru/domestic_history/text/1989125 (last access: 5 October 2025).

Mikhail Aleksandrovich Zenkevich (1886-1973), poet, translator and exponent of the Russian Acmeist movement. Born on 13 (1) June 1886 in Pugachëv (then in the Samara Governorate), he studied law at the University of St. Petersburg, where he came into contact with the lively literary scene of the time. In the early 1910s, he affiliated himself with the Acmeist poets' circle. His poetic production, although less well known than that of Gumilëv or Akhmatova, was appreciated for its attention to sensory detail and for the search for a balance between form and content; he published several collections that reflected both the Acmeist context and the influence of the European avant-garde. Of particular note was his work as a translator: among the many authors he translated were internationally renowned poets and prose writers such as Percy Bysshe Shelley, Rudyard Kipling, Walt Whitman and Victor Hugo, as well as other writers who represented symbols of 19th and 20th century Western culture. Thanks to his translations, Zenkevich made fundamental works for the understanding of European and American literature accessible to the Russian public, playing a key role in international cultural exchanges during the Soviet period. After the October Revolution, he continued to write and translate, managing to avoid the repressions that affected many of his contemporaries, and over the years he received various official awards for his efforts in popularising foreign works in the Soviet Union. He died on 14 September 1973 in Moscow. Zenkevich remains a significant figure in 20th-century Russian literary history, both as an exponent of a poetic strand attentive to a new formal classicism, and as a translator who allowed the Russian public to approach masterpieces of European literature. His works, while not as famous as those of other Acmeists, are now receiving renewed attention from Russian poetry and Translation Studies scholars.

Bibliography: M. Colucci, D. Rizzi, Gli adamisti: Gorodeckij, Zenkevič, Narbut, in Storia della civiltà letteraria russa, ed. by M. Colucci, R. Picchio, vol. II: Il Novecento, Turin, UTET, 1997, pp. 133-136; Vladimir Narbut, Mikhail Zenkevich: Stat’i. Retsenzii. Pis’ma, O. Lekmanov (intro.), M. Kotova (ed.), Moscow, IMLI RAN, 2008, pp. 3-17;

R.D. Timenchik, Zenkevich Mikhail Aleksandrovich, in Russkie pisateli. 1800–1917: Biograficheskiy slovar’, P.A. Nikolaev (gl. red.), Moscow, Bol’shaya rossiyskaya entsiklopediya, 1992, vol. 2, pp. 337-339.

Curator of the Russian translation: Michail Aleksandrovič Zenkevič

Russian translation publication date: 1930

Concise description of the paratext-directives' relation:

In Lunacharsky’s eyes, Herbert Wells emerges as a highly original and brilliant figure in contemporary European literature. His early novels, rich in scientific erudition and fantasy, earned him comparisons to a new Jules Verne, capable of captivating young people in particular. Works such as The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine enjoyed enormous success, but it soon became apparent that Wells was a far more serious author: his output matured into works characterised by a growing rejection of the bourgeois system, recognising its transitory nature and the urgency of eliminating its uglier aspects. Throughout his career, Wells distinguished himself by the evolution of his writing, moving from a superficial character psychology to a complex and profound depiction of human interiority, capable of carving a broad fresco of original and vivid characters. His works, especially the realistic ones of his later years, offer a careful and critical insight into English society, highlighting the psychological and social changes of the various strata, particularly between the avant-garde bourgeoisie and the intelligentsia. At the same time, Lunacharsky believes that, despite Wells’ considerable stylistic merits and narrative ability, his main flaw lies in the absence of a genuine revolutionary spirit: he desires a revolution, understood as a profound social change, but aims to achieve it in an evolutionary and gradual way, without breaking with the established order. Furthermore, Lunacharsky argues that this position, which lies between radical socialism and a form of reformist conservatism, limits Wells’ potential to drive real social change, making him more suited to observing and describing the reality of the present than to radically designing the future (cfr. D084).

Ilaria Aletto, Maria Zavyalova