Kuda idet francuzskaja intelligencija [P020]

Paratext collocation: "Literaturnyj kritik" [rivista], n. 2 – pp. 55-63

Paratext's typology: Article

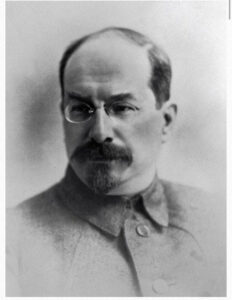

Author of the paratext: Lunačarskij Anatolij Vasil’evič

Author's bio:

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky (1875-1933) was a statesman, writer, translator, publicist, critic and art historian. He took an active part in the 1905-1907 Revolution and the October Revolution, and from October 1917 to September 1929 he served as the first People's Commissar for Education of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (RSFSR). In 1903, following the party split, he became a Bolshevik (he had been a member of the POSDR - Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party - since 1895). On 1 February 1930, he was elected a member of the USSR Academy of Sciences. In the period 1896-1898, the young Lunacharsky travelled between France and Italy. In 1898, he reached Moscow, where he began his revolutionary activities. A year later, he was arrested, exiled to Poltava and later transferred first to Kaluga, then Vologda and Totma. In 1904, after his exile ended, he went to Kiev and then Geneva, where he joined the editorial boards of the Bolshevik newspapers 'Proletariy' and 'Vperëd'. He soon became one of the Bolshevik leaders, close to Bogdanov and Lenin. Under the latter's leadership, he participated in the fight against the Mensheviks and took part in the 3rd Congress of the POSDR (where he presented a report on armed insurrection) and the 4th Congress (1906). In October 1905, he returned to Russia to carry out propaganda activities, worked at the newspaper 'Novaya Zhizn' and was soon arrested and tried for revolutionary agitation, but managed to escape abroad. From 1906 to 1908 he directed the art section of the magazine 'Obrazovanie'. Towards the end of the first decade of the 20th century, philosophical differences with Lenin escalated, soon escalating into a political conflict. In 1909, Lunacharsky helped found the extreme left-wing group Vperëd ('Forward') - named after the magazine it published - which brought together 'Ultimatists' and 'Otzovists', opposed to the presence of the Social Democrats in Stolypin's Duma and in favour of the withdrawal of the Social Democratic fraction. As the Vperëd group was expelled by the Bolsheviks, Lunacharsky remained outside the factions until 1917. Together with other Vperëd members, he collaborated in setting up party schools for Russian workers in Capri and Bologna. During this period he was influenced by the philosophers of empiriocriticism, a position harshly criticised by Lenin in his work Materializm i ėmpiriokriticizm (Materialism and Empiriocriticism, 1908). Lunacharsky, to the movement of the so-called God Builders (bogostroitely) and, as a reviewer of Western European literature for various Russian newspapers, took a stand against chauvinism in the artistic field. At the outbreak of World War I, Lunacharsky adopted an internationalist orientation, reinforced by Lenin's influence, and was among the founders of the pacifist newspaper 'Nashe Slovo'. At the end of 1915, he moved with his family from Paris to Switzerland. After the February Revolution of 1917, he returned to Petrograd, joined the Interdistrict Organisation of United Social Democrats (Mezhrayonnaya organizatsiya obyedinennych sotsial-demokratov) and was elected its delegate to the First Pan-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies. In July 1917, he joined the editorial staff of the newspaper 'Novaya Zhizn', founded by Maxim Gorky, with whom he had been collaborating since his return to Russia. After the events of the 'July Days', the Provisional Government accused him of treason and had him arrested. From August 1917, he worked on the newspaper 'Proletariy' (published in place of 'Pravda', which was suppressed by the government) and the magazine 'Prosveshchenie'. During the same period, he carried out intense cultural and educational activity among the proletariat, supporting the convening of a conference of workers' educational societies. In the early autumn of 1917, he was elected president of the cultural and educational section and deputy mayor of Petrograd, as well as becoming a member of the Provisional Council of the Russian Republic. On 25 October, at an emergency meeting of the Petrograd Soviet, he supported the Bolshevik line and delivered a heated speech against the right-wing Mensheviks and revolutionary socialists who had left the session. After the October Revolution, Lunacharsky joined the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) established by the Second Pan-Russian Congress of Soviets, taking up the post of People's Commissar for Education. In the first months after taking power, he actively defended the historical and cultural heritage. In response to the bombing of historical monuments in Moscow during the armed uprising, he tendered his resignation on 2 November 1917, which was, however, considered 'inappropriate' by the government and withdrawn the following day. He therefore remained People's Commissioner for Education until 1929. According to Lev Trotsky, he played a decisive role in bringing the old intelligentsia closer to the Bolshevik positions. Although he did not directly take part in the internal struggles within the party, Lunacharsky ended up aligning himself with the winning group, although he remained, according to Trotsky, 'an outsider figure in their ranks until the end'. In the autumn of 1929 he was removed from his post as People's Commissar for Education and appointed Chairman of the Scientific Committee of the USSR Central Executive Committee. In the early 1930s he directed the Institute of Literature and Language of the Communist Academy, the Institute of Russian Literature of the USSR Academy of Sciences and was among the editors of the Literary Encyclopaedia. He personally got to know several renowned European writers, including Romain Rolland, Henri Barbusse, Bernard Shaw, Bertolt Brecht, Carl Spitteler and Herbert Wells. In September 1933, he was appointed plenipotentiary representative of the USSR in Spain, but could not take up the post for health reasons. As deputy head of the Soviet delegation, he took part in the League of Nations Conference on Disarmament. He died of angina pectoris in December 1933, while travelling to Spain, near the French town of Menton.

- Ju.B. Borev, Lunacharsky, Moskva, Molodaya gvardiya, 2010.

- Lunacharsky, in Bolshaya rossiyskaya entsiklopediya: V 35 tt., 2004-2017, Ju. S. Osipov (gl. red.), Moskva, Nauch. izd. Bolshaya rossiyskaya entsiklopediya, 2011, T. 18 (Lomonosov - Manizer), pp. 139-140.

- Al. Deych, Lunacharsky, in Kratkaya Literaturnaya entsiklopediya, 1962-1978, A.A. Surkov (gl. red.), Moskva, Sov. entsikl., 1967, T. 4 (Lakshin - Muranovo), pp. 448-453.

- Lunacharsky, in Literaturnaya entsiklopediya: V 11 tt., 1929-1939, A.V. Lunacharsky (otv. red.), Moskva, OGIZ RSFSR, Gos. slovarno-entsikl. izd-vo "Sov. entsikl.", 1932, T. 6, coll. 626-635.

Date of the paratext: 1933

Author image:

Title of the original work translated into Russian: A la recherche du temps perdu

Publication date of the original work: 1913-1927

Country of the original work: France

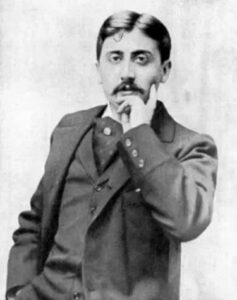

Author of the original text: Proust Marcel

Bio of the Author (original text):

Marcel Proust (1871 - 1922), famous French writer, born and died in Paris. exponent of literary Modernism, European. He came from an upper middle-class family (of Jewish descent on his mother's side); suffering from asthma from an early age, he attended the prestigious lycée Condorcet in Paris, chosen by the cultural elite of the time. After the death of his parents, he devoted himself completely to writing, isolating himself in his Parisian flat on Boulevard Hausmann. From a young age, he collaborated with literary and lifestyle magazines such as "Le Banquet", a magazine founded (1892) by a group of friends of Condorcet, the "Revue blanche", and from 1903 he wrote for "Le Figaro". Extensive excerpts of his works were published in the "Nouvelle revue française" from 1914. Beginning in his high school years, he assiduously frequented the salons of the Parisian upper middle class and aristocracy, whose snobbery he would later stigmatise, and in the Dreyfus affair he took the side of those who believed he was innocent.

His main work, À la recherche du temps perdu, consists of seven volumes published between 1913 and 1927. The first volume, Du côté de chez Swann, came out in 1913 at the author's own expense with the publisher Grasset (after André Gide's negative opinion had prevented its publication with Gallimard); from 1918 onwards, he published the remaining tomes of the novel with Gallimard: À l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleur, also Goncourt Prize, Le côté de Guermantes (2 vols., 1920-21), Sodome et Gomorrhe (3 vols., 1921-22). Only after Proust's death did the last three parts come out: La prisonnière (1923), Albertine disparue (1925, also called La fugitive) and Le temps retrouvé 1927. Through an autobiographical narrative, the novel explores the theme of time lost and found through involuntary memory, while also representing a fresco of French society of the time. Bibliography: Encyclopaedia Treccani, Marcel Proust.

Author image:

Title of the Russian translation: V poiskach za utračennym vremenem

Collocation of the translation: M.Prust V poiskach za utračennym vremenem, 1934-1938, Leningrad, Gosilitizdat

Translator's name: Adrian Frankovskij

Translator's bio:

Adrian Antonovich Frankovsky, Ukrainian-born intellectual and translator, one of the most important in the early decades of the Soviet Union, was born in 1888 in the village of Lobachev, near Kiev. In 1911, he graduated from the Faculty of History and Philology at St. Petersburg University. He taught in secondary schools and at the Leningrad Teachers' Institute, which was transformed into the 2nd Pedagogical Institute in 1918. From 1924 he was a professional writer and translator. His translations, especially from French and English, still retain their artistic value today and are republished. He always lived in Leningrad. From 17th-18th century English novelists he translated J. Swift, G. Fielding, L. Sterne, from 18th century French - D. Diderot, from 20th century authors - R. Rolland, Romain Rolland, André Gide, M. Proust. The initiative to translate Marcel Proust was an important merit of Frankovsky: at the end of the 1920s, he published the first part of Proust's Recherche - in his translation. In the 1930s, Frankovsky participated both as a translator and editor in the publication of Proust's Works. The first and third volumes (GIChL 1934-1938). He died in the Leningrad blokade, february 1942.

Russian translation publication date: 1934-1938

Concise description of the paratext-directives' relation:

In the long polemical article Kuda idet frantsuzkaya intelligentsia [Where is the French intelligentsia going] Lunacharsky traces the main stages of contemporary French culture for the readers of the newly founded literary journal ‘Literaturniy kritik’, in its second issue since its foundation. As stated in the paratext dedicated to him in the critic’s Sobranie sochineniy, the article in question originated from a transcript of a speech by Lunacharsky (8 February 1933) in response to the report of I.I. Anisimov on ‘André Gide and Capitalism’, delivered at a meeting of the USSR Organising Committee on 29 January 1933; both in the prolusion and in the article published in July 1933, we find ourselves in a historical moment in which, in the Soviet cultural-literary reviews, within a theoretical-formal and philosophical framework concerning the different souls of what would later become canonical socialist realism, defined after the First Congress of Soviet Writers in 1934, we find various testimonies of a wide-ranging and still general debate, lively since the end of 1933 (see in this regard, in LitKritik, the articles by P. Judin Lenin i nekotorye voprosy literaturnoy kritiki D134; V. Kirpotin O socialisticheskom realizme D135, also V. Kirpotin’s article in “Literaturnaya gazeta”, D094 ). In this context Lunacharsky, at that time no longer the People’s Commissar for Education, but somehow ‘demoted’ following the Great Turning Point to ‘chairman of the Scientific Committee of the USSR’s Central Executive Committee’, places Proust in his article between the loyal French communist intellectuals Gide and Barbusse (the latter, moreover, not exempt from ‘unsuccessful books’, p. 58), and Paul Valéry, whose work is judged with words of admiration and praise (‘he is a jeweller’ p. 62). In this early 1933 paper, placed after the theoretical-programmatic section in which the aforementioned critics wrote, Lunacharsky’s ideas on Proust, and on certain other unorthodox French writers, e.g. the aforementioned Valéry, stand out for a certain autonomy of the critic’s judgement, for the freedom of style and manoeuvre with which they are expressed within the cultural orthodoxy of the time, and, at the same time, they do not differ substantially from the biographical-literary sketches that Lunacharsky had published during the 1920s, also often very critical: his was in fact the first Soviet publication concerning Proust, in fact, in a 1923 obituary (Marsel’ Prust, “Krasnaya niva”, 1923 no. 6/11 February), then dedicated an article to him in 1924 (K charakteristike noveyshey frantsuzskoy literatury, “Pechat’ i revolyutsiya”, no. 2, pp. 17-26), just as some considerations on the Recherche were published in Pis’ma s Zapada [Letters from the West] in 1926 (first published as Pis’ma iz Parizha. Pis’mo tret’e, in “Krasnaya gazeta” nos. 28 and 29, February 1 and 2); in the mid-1920s, from his post of Narkompros, he facilitated the first translations of the Recherche into Russian for the famous and prestigious publishing house Academia, still located in Leningrad: those edited by Adrian Frankovsky and Boris Griftsov, of which the first two parts came out (V storonu Svana, Pod tenyu devushek v tsvetu, L. Academia 1927 and 1928); another parallel translation of the Jeunes filles en fleur came out for Nedra (Pod senyu devushek v tsvetu, transl. edited by L.Ja Gurevich, S. Parnok, with the collaboration of B. Griftsov, M. 1927); it should be noted that separate excerpts from the Recherche, (in particular from the Swan’ way) came out as early as 1924 for the journal “Sovremenniy Zapad” (No.5, pp. 103-125, the journal was the responsibility of Gorky and the publishing house Vsemirnaya literatura), in translation by M.N. Ryzhkina. In the early 1930s, Lunacharsky was still the promoter of the future new edition of the Recherche (M. Goslitizdat, 1934-1938, incomplete, and stopped at volume IV, Sodom i Gomorra). In the article from ‘Literaturniy kritik’ that we quote here, the Soviet critic states that “what makes Proust fascinating more than anything else are his extraordinary stylistic impulses and his exceptional vividness in reproducing memories”; he then states that “this can only be achieved by developing an extraordinary and subtle sensitivity and imaginative productivity. It is very interesting that Proust captures in his great work profoundly different social strata, different manifestations of human nature”, p. 60, even if to such initial generous statements he then hangs a cumbersome fringe of improprieties: “But Proust is a desperate and despicable snob. Almost half of the content of his famous series of novels boils down to the fact that various members of a semi-known aristocracy and miscellaneous riffraff [shval’] try to get into this or that salon, whereby a certain lady X considers herself to be a lady of high rank, but is not allowed to go to the house of lady Y, because lady Y is too high-born” (ibid.). Again, adds Lunacharsky: “Proust describes, yes, the weaknesses of the aristocracy: […] but the fact that a certain lord duke is bald and that some duchess is stupid certainly does not change the fact that these are divine or almost divine beings, whom the snobs treat with exceptional subservience; and if we take into account all the refined and sophisticated culture with which Proust is endowed, this lackey psychology of his is repugnant – the meanest I have ever seen in a writer.” (p. 61). Lunacharsky expresses himself here with remarkable expressive immediacy and with the stylistic independence that often distinguishes him in his critical paratexts/writings, far from any slavish adherence to pre-packaged critical-Marxist directives or formulae, whereby he succeeds as much in praising as in crushing (with an impressionistic and often genuinely ironic style) the French writer; in the second part, Lunacharsky appears almost annoyed at the unforgivably deferential attitude he recognises in Proust, all the more annoyed because the Soviet also recognises his considerable literary mastery, but is forced to insist on the ‘mortal sin’ of Marcel (author and narrator) and his best-loved characters in the Recherche: being a snob, being a lackey (a word often used by L. in his paratexts, even in the most unthinkable contexts, e.g., in relation to Giorgio Vasari and his biography) in relation to the aristocratic and rentier aristocrats of the Faubourg Saint-Germain; a sin, this, which the Soviet justifies only, and only partially, in closing, with the writer’s illness and his life as a recluse: that detachment from reality that gave him “that terrible limitation and that stamped him with the hateful stigma of social conservatism” (p.61). However, it should be noted that the very fact that L. returned to the Recherche many times over the course of ten years, and that he welcomed and facilitated the publication of its works in the USSR in the 1920s and early 1930s (until his rather sudden death in December 1933) as much as he could, positively judging its stylistic talent, is indicative of a peculiar “odi et amo” mentality on the part of the Soviet critic, who could not easily conceal his admiration for this French writer (see also, in this regard, P023)

Alessandra Carbone