Marsel’ Prust [P021]

Paratext collocation: V poiskach utračennogo vremeni, t. I. V storonu Svana – Moskva-Leningrad – Goslitizdat

Paratext's typology: Preface

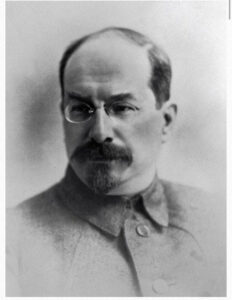

Author of the paratext: Lunačarskij Anatolij Vasil’evič

Author's bio:

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky (1875-1933) was a statesman, writer, translator, publicist, critic and art historian. He took an active part in the 1905-1907 Revolution and the October Revolution, and from October 1917 to September 1929 he served as the first People's Commissar for Education of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (RSFSR). In 1903, following the party split, he became a Bolshevik (he had been a member of the POSDR - Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party - since 1895). On 1 February 1930, he was elected a member of the USSR Academy of Sciences. In the period 1896-1898, the young Lunacharsky travelled between France and Italy. In 1898, he reached Moscow, where he began his revolutionary activities. A year later, he was arrested, exiled to Poltava and later transferred first to Kaluga, then Vologda and Totma. In 1904, after his exile ended, he went to Kiev and then Geneva, where he joined the editorial boards of the Bolshevik newspapers 'Proletariy' and 'Vperëd'. He soon became one of the Bolshevik leaders, close to Bogdanov and Lenin. Under the latter's leadership, he participated in the fight against the Mensheviks and took part in the 3rd Congress of the POSDR (where he presented a report on armed insurrection) and the 4th Congress (1906). In October 1905, he returned to Russia to carry out propaganda activities, worked at the newspaper 'Novaya Zhizn' and was soon arrested and tried for revolutionary agitation, but managed to escape abroad. From 1906 to 1908 he directed the art section of the magazine 'Obrazovanie'. Towards the end of the first decade of the 20th century, philosophical differences with Lenin escalated, soon escalating into a political conflict. In 1909, Lunacharsky helped found the extreme left-wing group Vperëd ('Forward') - named after the magazine it published - which brought together 'Ultimatists' and 'Otzovists', opposed to the presence of the Social Democrats in Stolypin's Duma and in favour of the withdrawal of the Social Democratic fraction. As the Vperëd group was expelled by the Bolsheviks, Lunacharsky remained outside the factions until 1917. Together with other Vperëd members, he collaborated in setting up party schools for Russian workers in Capri and Bologna. During this period he was influenced by the philosophers of empiriocriticism, a position harshly criticised by Lenin in his work Materializm i ėmpiriokriticizm (Materialism and Empiriocriticism, 1908). Lunacharsky, to the movement of the so-called God Builders (bogostroitely) and, as a reviewer of Western European literature for various Russian newspapers, took a stand against chauvinism in the artistic field. At the outbreak of World War I, Lunacharsky adopted an internationalist orientation, reinforced by Lenin's influence, and was among the founders of the pacifist newspaper 'Nashe Slovo'. At the end of 1915, he moved with his family from Paris to Switzerland. After the February Revolution of 1917, he returned to Petrograd, joined the Interdistrict Organisation of United Social Democrats (Mezhrayonnaya organizatsiya obyedinennych sotsial-demokratov) and was elected its delegate to the First Pan-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies. In July 1917, he joined the editorial staff of the newspaper 'Novaya Zhizn', founded by Maxim Gorky, with whom he had been collaborating since his return to Russia. After the events of the 'July Days', the Provisional Government accused him of treason and had him arrested. From August 1917, he worked on the newspaper 'Proletariy' (published in place of 'Pravda', which was suppressed by the government) and the magazine 'Prosveshchenie'. During the same period, he carried out intense cultural and educational activity among the proletariat, supporting the convening of a conference of workers' educational societies. In the early autumn of 1917, he was elected president of the cultural and educational section and deputy mayor of Petrograd, as well as becoming a member of the Provisional Council of the Russian Republic. On 25 October, at an emergency meeting of the Petrograd Soviet, he supported the Bolshevik line and delivered a heated speech against the right-wing Mensheviks and revolutionary socialists who had left the session. After the October Revolution, Lunacharsky joined the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) established by the Second Pan-Russian Congress of Soviets, taking up the post of People's Commissar for Education. In the first months after taking power, he actively defended the historical and cultural heritage. In response to the bombing of historical monuments in Moscow during the armed uprising, he tendered his resignation on 2 November 1917, which was, however, considered 'inappropriate' by the government and withdrawn the following day. He therefore remained People's Commissioner for Education until 1929. According to Lev Trotsky, he played a decisive role in bringing the old intelligentsia closer to the Bolshevik positions. Although he did not directly take part in the internal struggles within the party, Lunacharsky ended up aligning himself with the winning group, although he remained, according to Trotsky, 'an outsider figure in their ranks until the end'. In the autumn of 1929 he was removed from his post as People's Commissar for Education and appointed Chairman of the Scientific Committee of the USSR Central Executive Committee. In the early 1930s he directed the Institute of Literature and Language of the Communist Academy, the Institute of Russian Literature of the USSR Academy of Sciences and was among the editors of the Literary Encyclopaedia. He personally got to know several renowned European writers, including Romain Rolland, Henri Barbusse, Bernard Shaw, Bertolt Brecht, Carl Spitteler and Herbert Wells. In September 1933, he was appointed plenipotentiary representative of the USSR in Spain, but could not take up the post for health reasons. As deputy head of the Soviet delegation, he took part in the League of Nations Conference on Disarmament. He died of angina pectoris in December 1933, while travelling to Spain, near the French town of Menton.

- Ju.B. Borev, Lunacharsky, Moskva, Molodaya gvardiya, 2010.

- Lunacharsky, in Bolshaya rossiyskaya entsiklopediya: V 35 tt., 2004-2017, Ju. S. Osipov (gl. red.), Moskva, Nauch. izd. Bolshaya rossiyskaya entsiklopediya, 2011, T. 18 (Lomonosov - Manizer), pp. 139-140.

- Al. Deych, Lunacharsky, in Kratkaya Literaturnaya entsiklopediya, 1962-1978, A.A. Surkov (gl. red.), Moskva, Sov. ėncikl., 1967, T. 4 (Lakshin - Muranovo), pp. 448-453.

- Lunacharsky, in Literaturnaya entsiklopediya: V 11 tt., 1929-1939, A.V. Lunacharsky (otv. red.), Moskva, OGIZ RSFSR, Gos. slovarno-entsikl. izd-vo "Sov. entsikl.", 1932, T. 6, coll. 626-635.

Date of the paratext: 1934

Author image:

Title of the original work translated into Russian: A la recherche du temps perdu

Publication date of the original work: 1913-1927

Country of the original work: France

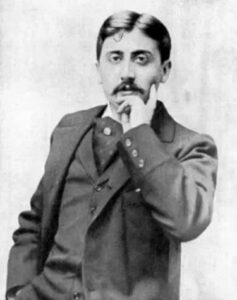

Author of the original text: Proust Marcel

Bio of the Author (original text):

Marcel Proust (1871 - 1922), famous French writer, born and died in Paris. exponent of literary Modernism, European. He came from an upper middle-class family (of Jewish descent on his mother's side); suffering from asthma from an early age, he attended the prestigious lycée Condorcet in Paris, chosen by the cultural elite of the time. After the death of his parents, he devoted himself completely to writing, isolating himself in his Parisian flat on Boulevard Hausmann. From a young age, he collaborated with literary and lifestyle magazines such as 'Le Banquet', a magazine founded (1892) by a group of friends of Condorcet, the 'Revue blanche', and from 1903 he wrote for 'Le Figaro'. Extensive excerpts of his works were published in the 'Nouvelle revue française' from 1914. Beginning in his high school years, he assiduously frequented the salons of the Parisian upper middle class and aristocracy, whose snobbery he would later stigmatise, and in the Dreyfus affair he took the side of those who believed he was innocent.

His main work, À la recherche du temps perdu, consists of seven volumes published between 1913 and 1927. The first volume, Du côté de chez Swann, came out in 1913 at the author's own expense with the publisher Grasset (after André Gide's negative opinion had prevented its publication with Gallimard); from 1918 onwards, he published the remaining tomes of the novel with Gallimard: À l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleur, also Goncourt Prize, Le côté de Guermantes (2 vols., 1920-21), Sodome et Gomorrhe (3 vols., 1921-22). Only after Proust's death did the last three parts come out: La prisonnière (1923), Albertine disparue (1925, also called La fugitive) and Le temps retrouvé 1927. Through an autobiographical narrative, the novel explores the theme of time lost and found through involuntary memory, while also representing a fresco of French society of the time. (Source: Encyclopaedia Treccani, 'Marcel Proust').

Author image:

Title of the Russian translation: V poiskach za utračennym vremenem

Collocation of the translation: M.Prust V poiskach za utračennym vremenem, 1934-1938, Leningrad, Gosilitizdat

Translator's name: Adrian Frankovskij

Translator's bio: Adrian Antonovich Frankovsky, Ukrainian-born intellectual and translator, one of the most important in the early decades of the Soviet Union, was born in 1888 in the village of Lobachev, near Kiev. In 1911, he graduated from the Faculty of History and Philology at St. Petersburg University. He taught in secondary schools and at the Leningrad Teachers' Institute, which was transformed into the 2nd Pedagogical Institute in 1918. From 1924 he was a professional writer and translator. His translations, especially from French and English, still retain their artistic value today and are republished. He always lived in Leningrad. From 17th-18th century English novelists he translated J. Swift, G. Fielding, L. Sterne, from 18th century French - D. Diderot, from 20th century authors - R. Rolland, Romain Rolland, André Gide, M. Proust. The initiative to translate Marcel Proust was an important merit of Frankovsky: at the end of the 1920s, he published the first part of Proust's Recherche - in his translation. In the 1930s, Frankovsky participated both as a translator and editor in the publication of Proust's Works. The first and third volumes (GIChL 1934-1938). He died in the Leningrad blokade, february 1942.

Russian translation publication date: 1934

Concise description of the paratext-directives' relation:

The contribution was first published as a preface to the new Russian edition of the Works of Marcel Proust, in M. Prust, Sobranie sochineniy, V. 1 V poiskach za utrachennym vremenem. V storonu Svana. Goslitizdat, L. 1934, pp. V-VII. This was Lunacharsky’s last work, and the article remained incomplete, so the editors accompanied it with the following note: “The last lines of the preface to the present collection of Marcel Proust’s works were dictated by Anatoly Vasilievich Lunacharsky on 24 December 1933, two days before his death, which prevented him from completing this work”. The same work was also published in ‘Literaturnaya gazeta’ of 5 January 1934 (no. 1/316, p. 3), an issue dedicated (not entirely) to the funeral of the Soviet intellectual and politician (on p. 2 we find: a copy of the condolence telegram sent by Romain Rolland; the account of the state funeral “Pochorony Bol’shevika”); below, on p. 3 of the newspaper is the contribution on Proust. In this last ‘Proustian’ piece of writing, which Lunacharsky worked on when he was not in the USSR, but in France (he was sent there on a diplomatic mission, and at that time he was staying on the coast, in Menton), we note a notable difference in style, but above all in content, with respect to the article published only a few months earlier in LitKritik (No. 2, 1933, see. P020), and in general with respect to the previous contributions that Lunacharsky had dedicated to the Recherche. The article is a posed analysis of the great work of the French writer, whose literary merits, stylistic elegance and refinement, artistic merits in the literary invention of the involuntary memory, and respect for his conception of art are rather emphasised. In the same way, Lunacharsky insists on Proust’s usefulness, and on his merits as a refined writer of realism; of course, a peculiar realism, all Proustian, which emerges in the article through the ironic device that mimics an imaginary squabble with a Western critic (an advocate of ‘art for art’s sake’), whose opinion is contested, to then shift the core of the hermeneutic problem instead to the possible and useful realism in Proust’s work: “Proustians will, of course, shrug their shoulders at these last questions of ours: -He doesn’t teach anything, he doesn’t want to give any message, he’s not interested in that. Oh, these Marxists!- And we respond to them: -And yet it does teach, the message is there, partly consciously. Oh, these deceitful formalists!-“. Proustian realism for L. therefore remains an indispensable trait, and not secondary to others, which he gladly emphasises: “In Proust, imagination, stylisation and sometimes outright fiction play an important role. However, in general, he is a realist’. One notices, however, reading the article, insights into stylistic-contextual traits that were decidedly controversial for Soviet critics of the first half of the 1930s: one among all, Proust’s famous ‘subjectivism’ (together with the accusation of ‘formalism’, this is and will in fact be one of the most recurrent criticisms), which here for Lunacharsky is instead a central, but estimable, trait of the author’s work: “For Proust, both from an everyday and philosophical point of view, the individual, above all his personality, comes first, and life is above all my life. Such subjectivism is, among other things, linked by the critic to the rationalist tradition of the French 17th century: “It is a superb 17th century realist subjectivism, very rationalist and very sensual. “(n.b. this line will also be taken up to some extent later by N. Rykova, see P024).

Lunacharsky then proceeds to insist on the sheer pleasure of reading Proust’s work, which focuses on the recovery of memory as an artistic, literary and almost cinematic operation : ‘In the foreground remains the pleasure of artistic creation, that is, the pleasure of a second life experience, slowed down and developed artistically, the pleasure of the creative work that is thus made fresh and complete’, the critic goes on to say: “That is why the element dearest to Proust, in his remarkable books, is precisely the cinematography of his memoirs. Here Proust has no equal. Lying in bed with his pen, he indulges in a kind of creative cinematography, equally powerful optically, acoustically, rationally and emotionally. He plays his part, and this play, ‘My Life’, is staged with unprecedented luxury, depth and love. The reproaches that even the friendliest critics have levelled at him: dragging tempos, too much detail, long sentences, often very un-French, etc. stem from this fundamental element of his work’. This writing by Lunacharsky, rich in metaphors, with a certain solemnity of writing and not without literary qualities of its own, does not therefore present a subtle techniques of ‘captatio benevolentiae’, tactics of domestication and mediation that can be linked to the already consolidated and used ‘strategies of appropriation’ typical of the editorial tradition of those years for literary texts or translated authors judged controversial by Soviet culture (see D088, D089, D094, D100) but at the same time it represents an isolated (and then largely ignored) exception, not the rule for the enthousiast final appretiation of Proust’s novel: the stylistic distance from paratexts concerning Proust published in 1934 (Makedonov, P022; Galperina, P023, and Lunacharsky’s own writings preceding this one), is evident, and can only be explained, probably, by the peculiar moment in which it was written, almost in articulo mortis. The full (posthumous) publication of such a sincere and profound endorsement of the French writer’s work (albeit incomplete, as the editors specify), is to be considered, perhaps, as a kind of condescending viaticum.

Alessandra Carbone