Marsel’ Prust [P022]

Paratext collocation: "Literaturnyj kritik" [rivista], 7-8 – pp. 154-177.

Paratext's typology: Article

Author of the paratext: Gal'perina Evgenija L'vovna

Author's bio:

GALPERINA, Evgenia Lvovna (1905 - 1982) - Russian Soviet critic, literary critic. She graduated from the Faculty of Social Sciences at Moscow State University in 1925 and began publishing from 1929. University lecturer in Western foreign literature (French, English) at Moscow State University; author of articles on foreign literature, especially French, of the 20th century. In the first 'Kurs zapadnoy literatury XX veka' (vol. 1, 1934; the work is in two volumes) Galperina wrote a chapter on the literature of France prior to the First World War. In 1949, she authored a short pamphlet on the principles of literary choices for self-taught readers (O principach vybora literaturnych proizvedeniy dlya chudozhestvennogo chteniya. V pomoshch' chtetsu - uchastniku chud. samodeyatel'nosti, M. Steklograiya OR VDNT im N.K. Krupskoj, 34 pp.); Galperina was also one of the first Soviet literary critics to deal with modern and contemporary literature of the peoples of Africa, and was editor and translator of some poems/author of paratexts to collections: V ritmach Tam-tama. Poèty Afriki (1961); Vremya plameneyushchich derevyev. Poèty Antil'skich ostrovov' (1961).

Bibliography: L.A. Zonina, Kratkaya Literaturnaya enciklopediya (1962-1978) ed. A.A. Sukov M. Sovet. Entsiklopediya, T.2 , 1964, p. 50.

-Official website of RGB Rossiyskaya gosudarstvennaya biblioteka

Date of the paratext: 1934

Title of the original work translated into Russian: A la recherche du temps perdu

Publication date of the original work: 1913-1927

Country of the original work: France

Author of the original text: Proust Marcel

Bio of the Author (original text):

Marcel Proust (1871 - 1922), famous French writer, born and died in Paris. exponent of literary Modernism, European. He came from an upper middle-class family (of Jewish descent on his mother's side); suffering from asthma from an early age, he attended the prestigious lycée Condorcet in Paris, chosen by the cultural elite of the time. After the death of his parents, he devoted himself completely to writing, isolating himself in his Parisian flat on Boulevard Hausmann. From a young age, he collaborated with literary and lifestyle magazines such as "Le Banquet", a magazine founded (1892) by a group of friends of Condorcet, the "Revue blanche", and from 1903 he wrote for "Le Figaro". Extensive excerpts of his works were published in the "Nouvelle revue française" from 1914. Beginning in his high school years, he assiduously frequented the salons of the Parisian upper middle class and aristocracy, whose snobbery he would later stigmatise, and in the Dreyfus affair he took the side of those who believed he was innocent.

His main work, À la recherche du temps perdu, consists of seven volumes published between 1913 and 1927. The first volume, Du côté de chez Swann, came out in 1913 at the author's own expense with the publisher Grasset (after André Gide's negative opinion had prevented its publication with Gallimard); from 1918 onwards, he published the remaining tomes of the novel with Gallimard: À l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleur, also Goncourt Prize, Le côté de Guermantes (2 vols., 1920-21), Sodome et Gomorrhe (3 vols., 1921-22). Only after Proust's death did the last three parts come out: La prisonnière (1923), Albertine disparue (1925, also called La fugitive) and Le temps retrouvé 1927. Through an autobiographical narrative, the novel explores the theme of time lost and found through involuntary memory, while also representing a fresco of French society of the time. Bibliography: Encyclopaedia Treccani, Marcel Proust.

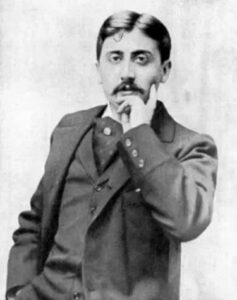

Author image:

Title of the Russian translation: V poiskach za utračennym vremenem

Collocation of the translation: M.Prust V poiskach za utračennym vremenem, 1934-1938, Leningrad, Gosilitizdat

Translator's name: Adrian Frankovskij,

Translator's bio:

Adrian Antonovich Frankovsky, Ukrainian-born intellectual and translator, one of the most important in the early decades of the Soviet Union, was born in 1888 in the village of Lobachev, near Kiev. In 1911, he graduated from the Faculty of History and Philology at St. Petersburg University. He taught in secondary schools and at the Leningrad Teachers' Institute, which was transformed into the 2nd Pedagogical Institute in 1918. From 1924 he was a professional writer and translator. His translations, especially from French and English, still retain their artistic value today and are republished. He always lived in Leningrad. From 17th-18th century English novelists he translated J. Swift, G. Fielding, L. Sterne, from 18th century French - D. Diderot, from 20th century authors - R. Rolland, Romain Rolland, André Gide, M. Proust. The initiative to translate Marcel Proust was an important merit of Frankovsky: at the end of the 1920s, he published the first part of Proust's Recherche in his translation. In the 1930s, Frankovsky participated both as a translator and editor in the publication of Proust's Works. The first and third volumes (GIChL 1934-1938). He died in the Leningrad blokade, february 1942.

Russian translation publication date: 1934

Concise description of the paratext-directives' relation:

Galperina’s article Marsel’ Prust is published in the 7-8 issue of “Literaturniy Kritik” 1934, on the eve of the First Congress of Soviet Writers, to be held from 17 August to 1 September of the same year. The scholar, also a university lecturer and author of a Kurs zapadnoy literatury XX veka [M., Gosud. Uchpedgiz, 1935], began her article by pointing out that “the names of Proust and Joyce have become in our discussions the standard symbols of bourgeois culture in the contemporary West. To lump the names of these two writers together as a single manifestation of poetics and similarity of style testifies to the often inaccurate notion of them in our literary circles”. In fact, Galperina recalls that the same names were present in D. Mirksiy’s article on Dos Passos a few months earlier, in which the critic did not skimp en passant on lapidary statements such as “the proletarian writer needs neither Proust nor Joyce”, еven more: “the Soviet critic certainly does not have to study Proust and Joyce” (Dos Passos, Sovetskaya literatura i zapad, in “Literaturniy kritik” N.1, 1933, p. 114, see also D135, D136); Let us add that a few weeks later, moreover, from the pulpit of the Congress of Proletarian Writers, the RAPPian critic Karl Radek in the course of his report entitled Sovremennaya mirovaya literatura i zadachi proletarskogo iskusstva [‘Contemporary World Literature, and the Tasks of Proletarian Art’, later published by GIChL, M. 1934] after again lumping Proust and Joyce together, he would dwell in particular on the latter’s usefulness (or uselessness), stating: “should we learn from those great writers – like Proust – the ability to delineate and describe the smallest movement of a man? That is not the point. The question is, whether we ourselves have our own high road to follow, in literature, or whether foreign works show us one […]. Of course, Proust is a better artist than our workers, our miners, he writes better than them, but what use are a thousand descriptions of salons and aristocrats to us, even if they come from the hand of a master? They move us less than the scenes depicting the struggle for our cause, even if they are written by our proletarian writers”. Ideally positioned (even on a strictly temporal level) between these interventions, Galperina, while expressing herself very severely on Proust, as we shall see, believes that it is instead useful to study him, using a mediation strategy that we could define as one of very partial and prudential acceptance. Indeed, the critic states in her article: “It is clear that not only the critic or the writer, but also the educated reader must be familiar with the major figures of the bourgeois West of our century.” Her aim is to seek out those aspects of these writers (in particular Proust), otherwise hastily ostracised, that can serve a careful analysis of Western society, opening, through their art, a privileged passage into that adverse world. What is more, the scholar must search “if there is not in these so openly decadent writers some purely literary side that can be used and exploited critically in our literature”. One might say this approach is very similar to Lunacharsky of the late 1920s – early 1930s; on the other hand, however, Galperina does not spare the usual colourful and decidedly negative epithets towards a bourgeois work and its controversial author, typical of the style of Soviet literary journals of those years: she introduces the French writer and his work by emphasising its impressive size, writing that the Recherche grew “book after book like a ‘monstrous tumour'” [chudovishchnaya opuchol’], p. 154); its main characters are ‘the crème de la crème of the parasitism of the bourgeois aristocracy’, or even an ‘encyclopaedia of bourgeois parasitism’ – the word ‘parasitism’ is, incidentally, repeated obsessively and overflowingly in the contribution, in a book that illustrates a ‘putrefied’, ‘rotting’ world (gniliy, gnilost’, are other words that recur frequently in the article and in the critical lexicon of the period). Nonetheless, Galperina recognises that Montesquiou’s epigone, the ‘sickly and idle writer’, had the artistic and writing skills that enabled him to become ‘one of the major ideologists and artists of the bourgeoisie at the time of its decadence, who was able to express certain aspects of bourgeois consciousness: decadent intuitivism, the struggle against reason and science, the subjectivistic sinking into one’s own ‘ego”’. In addition to the Proustian subjectivism and decadentism, sides on which much emphasis is placed, as Makedonov already does (see P023), Galperina, however, also emphasises the author’s (unintentional) endowment as a historian: “It is hardly ever mentioned that an entire epoch of French history is reflected in Proust’s work, that he is also a historian of the Third Republic […] Proust has so accurately and precisely portrayed these vain, idle, gluttonous French rentiers, eager to savour every little sensation, he has described them in every detail, and with such insight, that he has really managed to paint a comprehensive and very precise picture. And despite Proust’s narrowness, his novel is instructive for us, as it reveals and illustrates one of the most important sides of the capitalist era: the degeneration and parasitic rot of the upper echelons of society.’ In this contribution, therefore, Galperina employs hermeneutic strategies that could be, in part, ascribable to the future system of voprekism, later developed by G. Lukàcs (see the frequent use in the article of the adverb vopreki, or similar concessive morpho-syntactic structures, as in the following quotation: ‘One must read and study Proust, first of all because he is a wonderful representative of subjectivist and decadent art. […] Proust’s main value lies in the enormous and vivid fresco of social decay that we find in his novel, and in the fact that, although he was a defender of that society, as a talented writer he had to unmask its decrepitude, its death’, thus operating a ‘condemnation of capitalism’. In such considerations, however, it is necessary to emphasise a certain amount of contradiction, whereby syntagmas such as “marvellous representative of decadent art” are obscure in determining a definitive value judgement on the part of the scholar; this is what the technique of ‘partial and prudential acceptance’ seems to allow: a remaining in a continuous balance between acceptance/tolerance (Galtsova in her contribution even speaks more optimistically of a mediation strategy) and negative judgement tout-court, as we note in the aforementioned Karl Radek opinion, and as we note more generally in the directives of that period, cf. e.g. D143 by Usievich. This is also the case in the close of the article, in which a comparison is made between the Recherche and the works of the great French realist writers, in particular, Balzac: Proust’s apoliticality, passivity and above all ‘snobbery’ (according to the scholar) distinguish him from authors such as Balzac and Stendhal, and ultimately make him very close to those writers – ‘poisonous mushrooms’ in the definition of the critic Anisimov in the LitGazeta of the same year (D088); indeed, Galperina writes “Here we see a great difference between Proust, the artist of dying capitalism, and the writers of the bourgeoisie’s heyday. The problem of ‘progress’ preoccupied both Balzac and Stendhal. But they, by portraying the careerist aspirations of their young bourgeois, stigmatised the society that did not allow their heroes to spread their wings. Proust, on the other hand, unmasks bourgeois careerism, while affirming the inviolability of the salons of high society, defending the caste prejudices and privileges of the most raffinate upper middle class’. Again, the scholar states: “This is the cognitive value of Proust. If Balzac provided an ‘anatomy of capitalist society’ in its heyday, Proust created a kind of pathology manual of dying capitalism. And what we appreciate in Proust is that, being in essence an apologist for this society, as an artist he had to reveal its decadence, its death, its fate” (p. 177). And in confirmation of Proust’s ‘usefulness’ for Soviet literature, in the same issue of “Literaturny Kritik” 7-8, we point out an article by Boris Agapov dedicated to the Soviet essay, which, in a quirk, bears a thoroughly Proustian title, namely V poiskakh nastoyashchego vremeni.

Alessandra Carbone