Marsel’ Prust i realizm [P023]

Paratext collocation: "Krasnaja nov'" [rivista], 12 – pp. 199-217.

Paratext's typology: Article

Author of the paratext: Makedonov Adrian Vladimirovič

Author's bio: MAKEDONOV, Adrian Vladimirovich (1909 - 1994), was a Soviet literary critic, who began publishing in 1927. At first particularly active in the RAPP, from 1934 he was a member of the Soyuz pisateley and contributed to the major literary journals ("Literaturniy kritik", "Krasnaya nov'", "Literaturnoye obozreniye", etc.).) He wrote mainly on Soviet writers (M. Shaginian, V. Sayanov, V. Stavskiy, B. Kornilov, A. Fadeyev, etc.), but was also happy to express himself on foreign literature, especially French (M. Proust, L. Céline, A. Barbusse, etc.). He published articles on the history and theory of realism, directed against 'vulgar sociologism' in literature, especially in criticism of literary classics. He was arrested in 1937 and subjected to Stalinist repressions, sent to one of the camps in Vorkuta, where he then studied as a geologist, alternating his studies with work in the camp; freed in 1946, he returned to publishing from 1955, concentrating particularly on the criticism of Soviet poetry, such as the 'Smolensk school of poetry', and studied the work of N. Zabolotsky in particular. He was the author of the book Ocherki sovetskoy poèzii, 1960, Smolensk). Bibliography: L.N. Chertkov in Kratkaya Literaturnaya ènciklopedija (1962-1978) ed. A.A. Sukov, M. Sovet. Èntsiklopediya, T.4 , 1967, p.516-517.

Date of the paratext: 1934

Paratextual directives:

- D088 - O nasledstve, o "novatorstve" (articolo 1, di I. Anisimov) [LINK]

- D094 - Diskussija o socialističeskom realizme [LINK]

- D097 - Pisatel' i revoljucionnaja teorija [LINK]

- D135 - O socialističeskom realizme (di V. Kirpotin) [LINK]

- D137 - Kritika i lozung socialističeskogo realizma (di M. Rozental’, E. Usievič) [LINK]

- D144 - Socialističeskij realizm i problema mirovozzrenija i metoda (di I. Nusinov) [LINK]

- D146 - Rešenija XVII parts''ezda VKP(b) i nekotorye zadači literatury [LINK]

Title of the original work translated into Russian: A la recherche du temps perdu

Publication date of the original work: 1913-1927

Country of the original work: France

Author of the original text: Proust Marcel

Bio of the Author (original text):

Marcel Proust (1871 - 1922), famous French writer, born and died in Paris. exponent of literary Modernism, European. He came from an upper middle-class family (of Jewish descent on his mother's side); suffering from asthma from an early age, he attended the prestigious lycée Condorcet in Paris, chosen by the cultural elite of the time. After the death of his parents, he devoted himself completely to writing, isolating himself in his Parisian flat on Boulevard Hausmann. From a young age, he collaborated with literary and lifestyle magazines such as "Le Banquet", a magazine founded (1892) by a group of friends of Condorcet, the "Revue blanche", and from 1903 he wrote for "Le Figaro". Extensive excerpts of his works were published in the "Nouvelle revue française" from 1914. Beginning in his high school years, he assiduously frequented the salons of the Parisian upper middle class and aristocracy, whose snobbery he would later stigmatise, and in the Dreyfus affair he took the side of those who believed he was innocent.

His main work, À la recherche du temps perdu, consists of seven volumes published between 1913 and 1927. The first volume, Du côté de chez Swann, came out in 1913 at the author's own expense with the publisher Grasset (after André Gide's negative opinion had prevented its publication with Gallimard); from 1918 onwards, he published the remaining tomes of the novel with Gallimard: À l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleur, also Goncourt Prize, Le côté de Guermantes (2 vols., 1920-21), Sodome et Gomorrhe (3 vols., 1921-22). Only after Proust's death did the last three parts come out: La prisonnière (1923), Albertine disparue (1925, also called La fugitive) and Le temps retrouvé 1927. Through an autobiographical narrative, the novel explores the theme of time lost and found through involuntary memory, while also representing a fresco of French society of the time. Bibliography: Encyclopaedia Treccani, Marcel Proust.

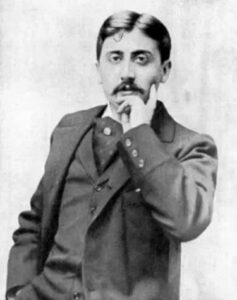

Author image:

Title of the Russian translation: V poiskach za utračennym vremenem

Collocation of the translation: M.Prust V poiskach za utračennym vremenem, 1934-1938, Leningrad, Gosilitizdat

Translator's name: Adrian Frankovskij,

Translator's bio:

Adrian Antonovich Frankovsky, Ukrainian-born intellectual and translator, one of the most important in the early decades of the Soviet Union, was born in 1888 in the village of Lobachev, near Kiev. In 1911, he graduated from the Faculty of History and Philology at St. Petersburg University. He taught in secondary schools and at the Leningrad Teachers' Institute, which was transformed into the 2nd Pedagogical Institute in 1918. From 1924 he was a professional writer and translator. His translations, especially from French and English, still retain their artistic value today and are republished. He always lived in Leningrad. From 17th-18th century English novelists he translated J. Swift, G. Fielding, L. Sterne, from 18th century French - D. Diderot, from 20th century authors - R. Rolland, Romain Rolland, André Gide, M. Proust. The initiative to translate Marcel Proust was an important merit of Frankovsky: at the end of the 1920s, he published the first part the first part of Proust's Recherche in his translation. In the 1930s, Frankovsky participated both as a translator and editor in the publication of Proust's Works. The first and third volumes (GIChL 1934-1938). He died in the Leningrad blokade, february 1942.

Russian translation publication date: 1934

Concise description of the paratext-directives' relation:

In this article, the literary critic Adrian Makedonov takes up the discussion on the theme of realism in Proust, on which Lunacharsky (1933, 1934) and Galperina (1934) had already commented, to focus, in the end-of-year issue of the journal (this is no. 12 of “Krasnaya nov'”), rather on the French writer’s lack of realism, which is deeply criticised. After a rapid sociological excursus on the ‘parasitic’ and decadent character of the heroes of Proust’s novel, in which the critic deconstructs what he calls the apparent ‘poetization of wealth’ of these characters (the cultured upper middle class, the French aristocracy) dear to Proust and his Marcel, Makedonov corroborates his theses by quoting passages, in particular from the second volume of the Recherche, À l’Ombre des jeunes filles en fleur, passages concerning observations on the nature of money ‘provided with a smile’, in which the protagonist-rentiers, deprived of worries and fatigue, dispose of money that is apparently ennobled by the culture, the inclination to the arts, the disinterested kindness that the status of their masters guarantees, and which is very different from the idea of ‘money without a smile’ of the petty-bourgeois and the accumulators. In this regard, Makedonov also quotes a famous passage from Marx (from The Holy Family, in one of the analyses of annuity capital at the height of the development of industrial capitalism) in which he explains the nature of the purely consumerist wealth of the French rentiers, who understood it as a mere exercise of ‘monstrously voluptuous whims’ (Makedonov, p. 203). The complete detachment from any active mechanism of production of this social class thus generates for the Soviet critic the illusion that money, on which the prosperity of Proust’s world rests, produces itself, hence the chimera of being able to withdraw completely into oneself, into ‘one’s own’ solipsistic and individualistic world, p. 204); the first question the critic of “Krasnaya Nov'” asks himself, faced with the magnificent fortunes of Proust’s upper-class characters, the dukes of Guermantes, the princes of Saint-Loup, the barons of Charlus, is how these fortunes came about, and where all this money, squandered so nonchalantly, came from: he is interested in the capital that allowed Proust to have Swann dine every day at the Jokey Club, to have the Duchess of Guermantes organise his famous matinées, that makes Marcel’s grandmother, an otherwise so innocent and good-natured character, take her grandson on holiday every year to the Grand Hotel in Balbec. The critic writes: “How all this wealth is created, Proust does not even think of telling. Nor does it describe how it is that this wealth is kept away from the ‘dark crowd”. In this regard, the critic, who emphasises the complete absence of historicism and attention to economic-social relations in Proust’s great work, dwells, however, on the quotation of a passage from the Recherche in which he recognises a certain stylistic and literary talent in the French writer’s creation of the successful image that transforms the restaurant of the Grand Hotel into a ‘social aquarium’ in which the rich are inside and the poor “invisible in the shadows, squeezes against its glass wall to contemplate, slowly swaying in swirls of gold, the luxurious life of those people, for the poor no less extraordinary than that of the strangest fish and molluscs…will the glass wall forever protect the feast of the marvellous animals, or will the dark crowd that eagerly peers into the night not come to catch them in their aquarium and eat them?” (Proust, p. 308 ). Makedonov, while admitting that ‘the metaphor was very well suited to Proust’, is not overly impressed by it, as he states that, in the end, the ‘tropical fish’ (upper middle class, nobility of the Faubourg Saint Germain) are the real heroes of the novel. The fact that Proust ironizes the various Verdurin, Legrandin, Swann, that he lingers sarcastically over the faults of his own class, does not in the slightest move Makedonov’s convictions, who considers him a snob (accepting Lunacharsky’s lesson from 1927 to 1933) and for whom ‘all Proust’s criticism of his own world never went beyond the bounds of mild self-criticism. Proust himself is one of those men whose profession is idleness, and for whom the exponents of the nobility he describes remain the only beings that really interest him, the only ‘heroes’ of his novel, the only bearers of humanity, wit, feeling, beauty’ (p. 205). Having dismissed the socio-economic problem, Makedonov concentrates on the stylistic one with regard to the French writer’s realism, which gives the article its title, and which would in reality be an ‘anti-realism’ or a non-realism for the critic of “Krasnaya nov'”: far from the examples of the great French (Balzac) and from the great Russians’ capacity for fine and realistic psychological analysis (Tolstoy and Dostoevsky are readily quoted, as in Anisimov’s articles and Kirpotkin’s contribution, see D088, D094), Proust fragments reality into thousands of constantly evolving semi-realities (there are no characters, no objectivity, in this novel but a flow of psychological facets, a Bergsonian philosophical inheritance, so that the Odette-cocotte at the beginning of the book later becomes Odette-grand dame, and so it will be for Saint-Loup, for Gilberte, etc.); If Proust cannot and cannot completely free himself from a description of reality, this is ultimately instrumental and subject to a procedure of formal aesthetisation and transformation/filtration (of exaggerated subjectivism, close to mysticism) of reality: “the transformation of the ‘dust of everyday life’ into ‘magical gold dust’ is precisely the essence of ‘realist’ mysticism in the Proustian method. This is done, in the first place, by embellishing and aesthetising said prosaic dust […] Proust is wont to compare real things with an image or an aesthetic experience, so Odette is filtered through a Botticelli painting, a butterfly asleep in the corner of a window, against a background of sky and sea – with the artist’s signature beneath a Whistler painting’ (p. 210). For Makedonov, Proust’s is a work in which solipsism, subjectivism and egoism are central, therefore, and ultimately do not communicate anything, are not useful, and are not to be considered plausible literary novelties. In this the critic naturally traces the disquisitions on literary realism, in opposition to modernisms and ‘formalisms’ already much discussed during 1933 and 1934, also in relation to the definitions of ‘socialist realism’ and the debates on ‘literary classics’: see in this regard D097, D135, D137, D144, D146. Makedonov therefore concludes severely: “Proust is the last attempt of the French bourgeoisie to create great art. After the war, in the conditions of the general crisis of capitalism, these attempts were no longer repeated, and the very ‘illusion of human wealth’ on which Proust’s attempt was based all too clearly failed, Proust himself was but proof of this failure’ (p. 217). The Soviet critic uses the Russian term ‘bankrotstvo’ at this juncture, which is very eloquent given the general tone of the contribution.

Alessandra Carbone